Every month an exclusive edition run of a photograph by an artist featured in Don't Take Pictures magazine is made available for sale. Each image is printed by the artist, signed, numbered, and priced below $200.

We believe in the power of affordable art, and we believe in helping artists sustain their careers. The full artist receives the full amount of the sale.

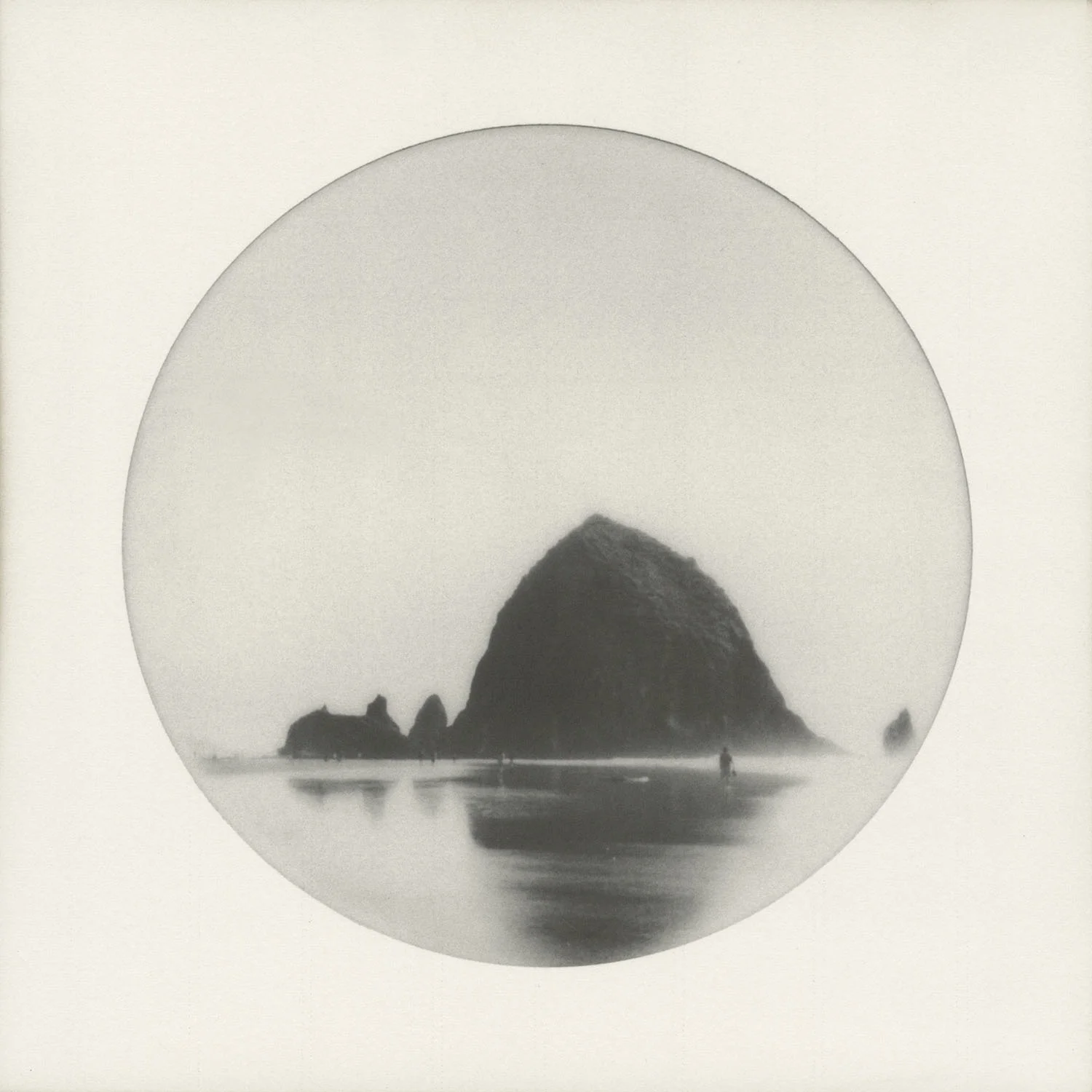

We are pleased to release November's print, "Ecola" from Catie Soldan Read more about Soldan’s work below.

Purchase this print from our print sale page.

Catie Soldan

Ecola

Archival pigment print from kalitype original

6 x 6, signed and numbered edition of 5

$100

Catie Soldan’s photographic series, Desert to Sea, began unintentionally. In 2015, with no expectations or preconceived ideas, Soldan set out on that classic American adventure—the road trip. Camera in hand, she and her mother traversed southern Utah, hiking through Canyonlands, Arches, Capitol Reef, Bryce Canyon, and Zion National Parks. A few months later, she took off again on yet another road trip adventure, this time to the Pacific Northwest with her sister. Traveling to Oregon for the first time, she made images throughout the Columbia River Gorge, Ecola State Park, and Cannon Beach. The polar opposite to the arid desert landscape of the Southwest, Soldan fell in love with Oregon’s lush green forests and salty coastal air.

Having seen and documented these two disparate yet equally magical landscapes, Soldan returned home and began the long process of image editing. Initially, she viewed these photographs as two separate bodies of work from two very separate trips. Yet throughout the editing, parallels emerged. Geological formations, each shaped over millennia, mimicked each other in their sculptural beauty; horizons aligned; both landscapes possessed a similar sense of primordial mystery. Desert landscapes, faced with continual and ever-changing erosion, reveal canyons, mesas, buttes, and hoodoos. Canyons with water flowing through them, long since evaporated and left barren, ultimately present a landscape not so dissimilar to the Oregon coastline, with its sea stacks and natural arches rising from the ocean floor, also formed over millennia, shaped by wind and water. Soldan imagined how these desert canyons might have looked long ago, when water flowed freely and consistently through them. The ancient and complex geological formations of both landscapes merged for her, shapes echoing one another, ultimately seeming as one and the same enigmatic landscape.

Blue Mesa

A native Chicagoan, Soldan spent her undergraduate years at the Savannah College of Art and Design in before moving to Santa Fe, a place she has called home for the last five years. Even after this length of time, the Southwest, for Soldan, is both familiar, yet still new and exciting—a landscape where she feels discoveries are yet to be made. And so, like a stranger in a strange land, Soldan began to document the vast desert landscape, with its seemingly infinite horizons.

Soldan used Polaroid film for her photographs, thoughtfully meshing image with process. Shooting with instant film seems at once old-fashioned and cutting edge. Polaroid film offers a dreamy quality that is hard to duplicate. Its uniqueness lies not only in its one-of-a-kind nature, but also in its old-film aesthetic. HDR clarity and sharply defined crispness are not an option. Imperfections abound—strange artifacts, inconsistent development, and softness are part of the lure for those who do not have access to a traditional darkroom, but who “desperately want to work with film as Soldan did. Beautifully and seamlessly, this medium connects with her subject matter, which, through Soldan’s vision, appears timeless. The inconsistent Polaroid development, which sometimes appears as a fading of the image, suggests both a vanishing and a vulnerable landscape.

Haystack

More importantly, perhaps, instant film requires an eye for composition, which is no small feat when photographing something as expansive and filled with as many choices as the immense Western landscape. Soldan composed her images in-camera and, like many photographic artists who print in ‘alternative’ 19th century processes, Soldan’s image-making was not even close to complete at the click of the shutter. She scanned these original Polaroids to make them larger, yet they remain—by contemporary standards—relatively small. No larger than six inches across, Soldan made the choice to move away from the typical mural-like landscape imagery; in so doing, she manages to transform these sweeping limitless landscapes into intimate gem-like objects we hold in our hands. She then chose to print these in the kallitype process, a contact printing technique that uses a specific emulsion that is brushed on watercolor paper, and exposed only by UV light. Gold-toning these kallitypes not only made them more archival, but added a cooler hue to the images.

From start to finish Soldan’s choices serve to create a fascinating window into a soft, cinematic landscape that seems both foreign and familiar. She distinguishes the Southwestern and coastal images by their shape and energy. Soldan made the Southwest images square as that environment seemed more masculine to her; in doing so, she suggests that the Western desert, in our dreams and imagination, still resonates as an untamed and unclaimed frontier, at one with the masculine ethos of rugged individualism, autonomy, and freedom. The coastal images Soldan made with round film because she felt that projected a more feminine energy, which meshes with the life-giving force of water, at one with the feminine aspects of creation.

The Needles

These photographs are mostly devoid of people, and markers of time are non-existent. The Polaroid film with its faded quality, as well as the antique kallitype process, helps to create this timeless picture where we as viewers become strangers in this strange land, too. The only clue that we might be looking at 21st century landscapes is one image in which a lone girl stands silhouetted on an Oregon beach, cell phone in hand, her shape and shadow echoing that of the rock formations that surround her. In the last image of the series, we see a girl, back to the camera, looking across to the endless sea through coin-operated binoculars. We are again reminded that this otherworldly landscape of unimaginable beauty is of the here and now, yet also part of our past. This image, in particular, makes us want to see what this girl sees. We are reminded that these dynamic landscapes, like people, remain part of our past, our present, and looking ahead, as part of an unknown and unseeable future, with discoveries yet to be made.

Diana H. Bloomfield, a native North Carolinian, is a photographer, independent curator, and writer. She currently lives and works in Raleigh, North Carolina.

This article first appeared in Issue 7.