When we think of a photograph, we often associate it with longevity, taking for granted the fact that the captured image will outlive our own unstable recollections. This illusion of permanence belies the profound fragility of photographs, objects that remain intact only with careful and routine conservation in museums and collections around the world. As we move into an increasingly digital world where images are scanned, shared, and forgotten, the future of historical photographs—made on paper, glass, and metal plates—hangs in the balance. In the modern age, photo conservators are arguably more crucial than ever before, becoming guardians of a cultural and artistic heritage that is in danger of slipping from our fingers.

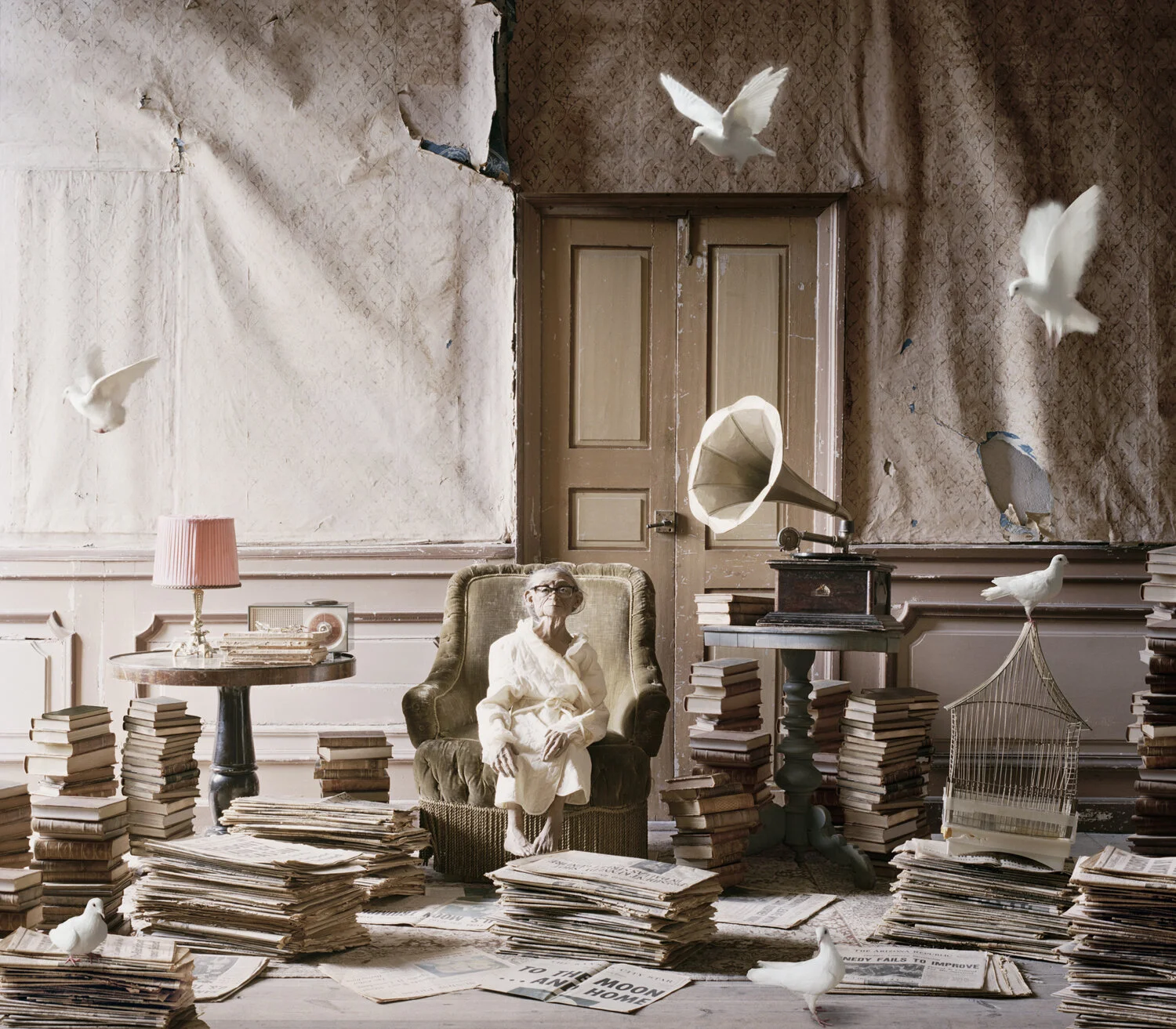

Tintype by Amy Brost Photo: Ellyn Kail

I visited the Conservation Center at New York University’s Institute of Fine Arts on Manhattan’s Upper East Side, and had the opportunity to go behind the scenes with Laura Panadero and Amy Brost, second and third year graduate students respectively with a concentration in photograph conservation. The program, explained academic advisor Kevin Martin, is the oldest of its kind in the nation, and graduates receive both a Masters in Art History and an Advanced Certificate in Conservation. Students arrive at the Center with backgrounds in laboratory science, studio art, and art history, each of which will play a key role in their education and career.

Students learn a range of conservation treatments in the program, from cleaning and mending to constructing safe housings for fragile materials. To choose the right materials to use in their treatments, Brost and Panadero are being trained to identify any conceivable photographic process. Holding a daguerreotype from her own study collection in her hand, Brost called my attention to the metallic sheen of the image and the tarnish marks that run along the borders of the frame. Characteristics like these help conservators determine the chemical process used to create an object so they can take appropriate steps to preserve it. Microscopes too are used to examine photographs. For instance, in a salted paper or platinum print, the metallic image material is embedded in the paper fibers. These fibers are clearly visible under magnification. On the other hand, in a silver gelatin print, which includes an intermediate layer of barium sulfate (also called baryta, the compound responsible for the photograph’s bright white tones), the baryta layer will mask such fibers. Looking for paper fibers under magnification is one way to distinguish between these two photographic processes.

In addition to visual examination, photograph conservators can use scientific instruments to aid their analysis. For example, pointing a handheld device called an XRF (which stands for X-ray fluorescence) spectrometer at a photograph can determine which metals are present within the image. Common ones are silver, platinum, and palladium, but some pigment-based photographic images have no metals at all. In those cases, it is the absence of a metal that provides a valuable clue.

Determining the technique used to create an image is a critical part of the process, and will often inform the treatment of a photograph. Introducing humidity may be a viable option for treatment of a curled or distorted gelatin silver photograph intended to lay flat. On the other hand, applying any amount of water to a 19th-century albumen print may be a dangerous game, exacerbating microcracks in the albumen (a binding agent made from egg whites).

The Conservation Center at New York University, courtesy of Amy Brost

“Conservation is all about understanding how artwork is made and how it’s manufactured. It’s not primarily about ‘What does the imagery mean?’” Martin reminded me. He mentioned that someone with a background in science could easily mistake many of the Center’s rooms for a science lab. But the role of the conservator, though clinical, is colored most by a deeply felt sense of human and artistic heritage, and every technical move is carefully calibrated to preserve that object’s cultural value.

American conservators must follow a set of ethical guidelines as established by the American Institute for Conservation of Historic & Artistic Works, but one photograph could doubtless inspire divergent treatment proposals, each of which is based on equally moral lines of thought. Panadero asked me to consider, for example, a photograph that has been in a fire and fringed with a layer of soot. Where one conservator might clean it for aesthetic purposes, another might suggest there is historic value in the ash itself. For this reason, the most ideal treatment is one that is reversible or re-treatable. Meticulous documentation during treatment enables future conservators to understand what was done to the photograph in the past. Students in NYU’s conservation program must catalogue each step in the process of conserving a photograph, recording everything from the instruments used to the reason for undertaking the treatment. The Center has a digital photo studio, where conservators-in-training record the object at various stages throughout each treatment.

19th-century daguerreotype from Amy Brost's study collection of photographs, courtesy of Amy Brost

During my visit, Brost was working on repairing a print that had been ripped entirely in half. To mend the tear, she used water-soluble adhesives like gelatin and wheat starch paste, applying a minuscule amount beneath a microscope. Her instructors will notice even the smallest error in repaired tears, pointing out a loose paper fiber that needs to be tucked into the mend. Every single element of the photograph must be protected to preserve the integrity of the object as a whole and the image that it depicts.

The field of art conservation has transformed alongside photography itself. Where students at the Conservation Center once turned first to microscopes to identify unknown pigments, they can now use other instruments, such as the XRF spectrometer. The microscopy room, Martin said to me wistfully, is now mostly used for guest lecturers.

As I walked out of the building to hail a cab, I realized that this was the first time that I had ever seen a daguerreotype in person. I could have touched it, given that it was protected by a layer of glass (daguerreotype images can be easily damaged by any abrasion). I have seen hundreds of daguerreotype images on my computer screen or projected on a wall, and yet the tender image of father and child that Brost described as “flea market quality” will be more deeply imbedded in my memory simply because it was a real, tangible object that lay before me. Emerging conservators like Panadero and Brost are preserving not only 175 years of human history, they are also safeguarding the exquisitely basic material quality of photography, a function that continues to delight us regardless of whether we are visiting a museum or leafing through a family photo album.

This article first appeared in Issue 4.

Ellyn Kail is a photography writer and Editorial Assistant at Feature Shoot. She lives in Bronxville, New York with her wonderful husband and beloved pit bull mix.