The week leading up to the Armory show is hectic, and more than a few galleries, with their energies dedicated to exhibiting at the show, slide through March barely able to keep their heads above water. Still, the energy is palpable in many spaces as gallerists and collectors prepare for a weekend of art. Last Thursday, the Leica Gallery buzzed at its opening for Amy Arbus and Curtice Taylor.

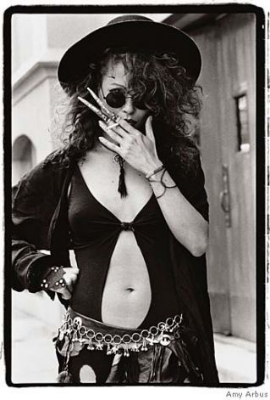

The Clash. Broadway. 1981. Amy Arbus.

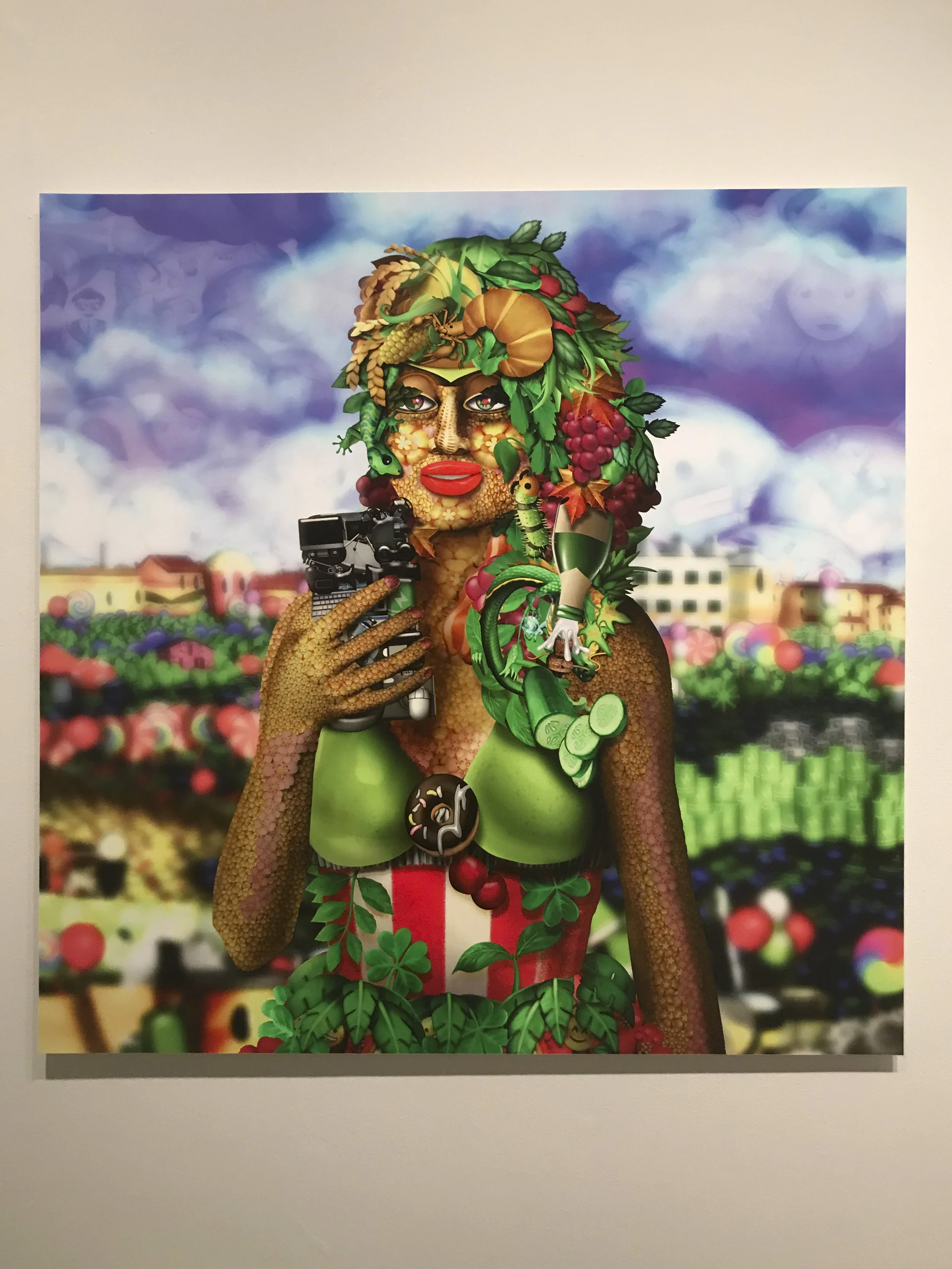

I assumed that most of that energy came from people coming to see Arbus’s work, but Taylor’s work, with its textures and its sometimes fervid examination of color, played a perfect counterpoint. Here were Taylor’s garden photographs, capturing seemingly timeless landscapes, alongside Arbus’s black and white portraits on the streets of the city. The juxtaposition was striking.

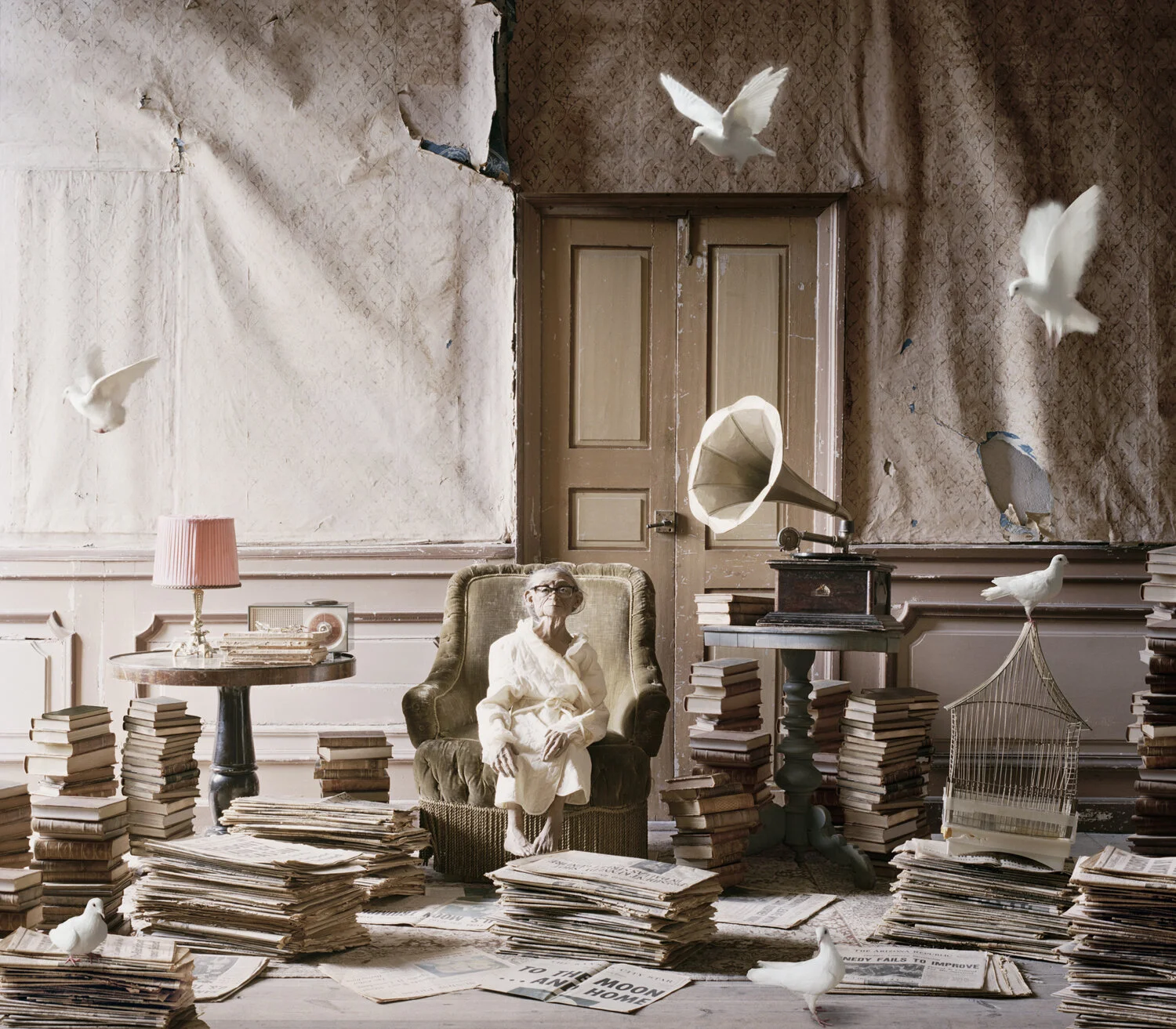

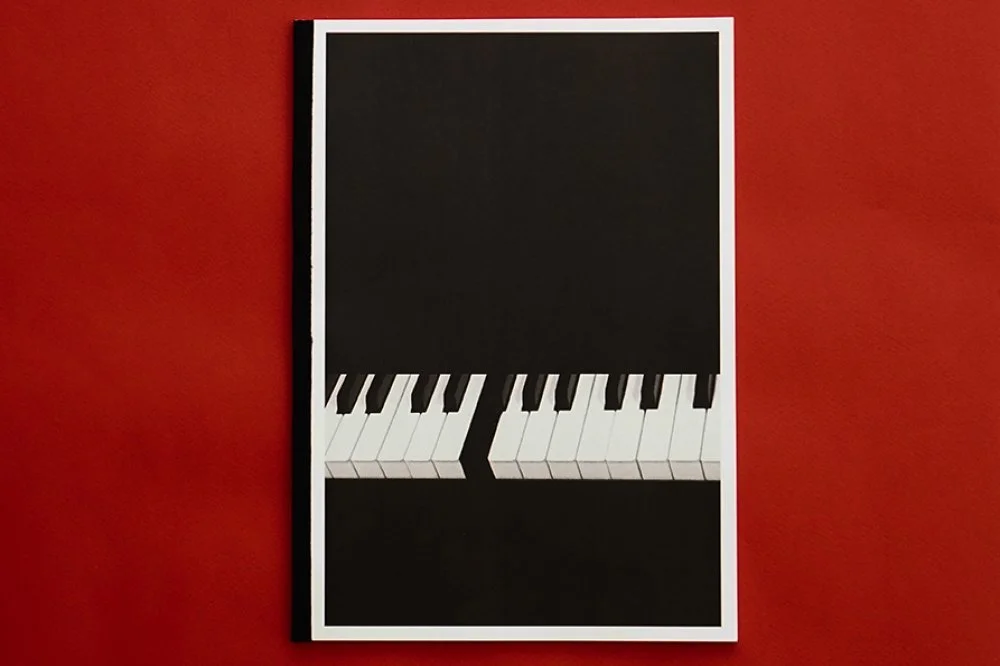

Curtice Taylor.

Surreal Spring. Curtice Taylor.

Taylor has a strong sense of contrast and depth. While he might sacrifice a certain degree of precision in the lines demarcating different spaces, the result is a seamless dream, where flowers and light and sky melt into each other. Taylor shifts the pathways and hedges off-center, resulting in images where space contracts toward the viewer. Similarly, in Surreal Spring, trees frame and hem in the view, and the neat, clean hedgerow beneath the chaotic branches above serve to ground the image in contrasts. While the neat line across the top of the hedge suggest a solid and permanent space, it serves instead as a foundation for an open view of light and sky beyond. Still, the sky is framed by the trees on either side and their jumbled branches above. This is a gateway to a timeless world.

If Taylor aims for the universal, Arbus aims for the particular, if not outright peculiar. Her portraits from the 80s speaks to our culture’s current obsession with that time period, but their composition and their subjects carry them far beyond trend. Visitors will recognize many of the locations, and New Yorkers will recognize the eccentrics, but Arbus ultimately presents a rumination on the city. We aren’t in the territory of Whitman or Ginsberg, who press for limitless catalogues of difference and idiosyncrasy. Instead, we’re in an earnest (if at times playful) cityscape. You get the sense that the subjects are serious about the image they are portraying of themselves and that the photographs permeate more than the veneer of life on the streets. In Fingernail Extensions for instance, we are greeted by a woman with unusual fingernails smoking a cigarette, and while she may not embody the fame of Madonna or Elvis Costello, her portrait is no less sincere and no less important. All of Arbus’s subjects are, on the one hand, singular, decked out in styles that define their personalities, but, on the other hand, leveled, hemmed in by a city whose contours embrace such a diversity of experiences that no single one can claim to be king or queen, heir to the empire. The value of the exhibit is the sense that Arbus’s subjects are familiar, and they are likely familiar simply because we see ourselves (albeit perhaps from another time) in them.

Fingernail Extensions. 23rd Street and Eighth Avenue. 1988. Amy Arbus.

Peter McGough and David McDermott. Spring Street and West Broadway. 1983. Amy Arbus.

Go to see Arbus, but do not neglect Taylor. If you do, you’ll miss the contrast, and you will ultimately miss the door to the city swinging open before you.

On the Street 1980-1990 and Transforming Nature: Gardens and Landscapes, is on view at Leica Gallery in New York City through April 19, 2014.

Roger Thompson is the Senior Editor for Don’t Take Pictures, an art critic, and Professor at Stony Brook University in Long Island, New York.