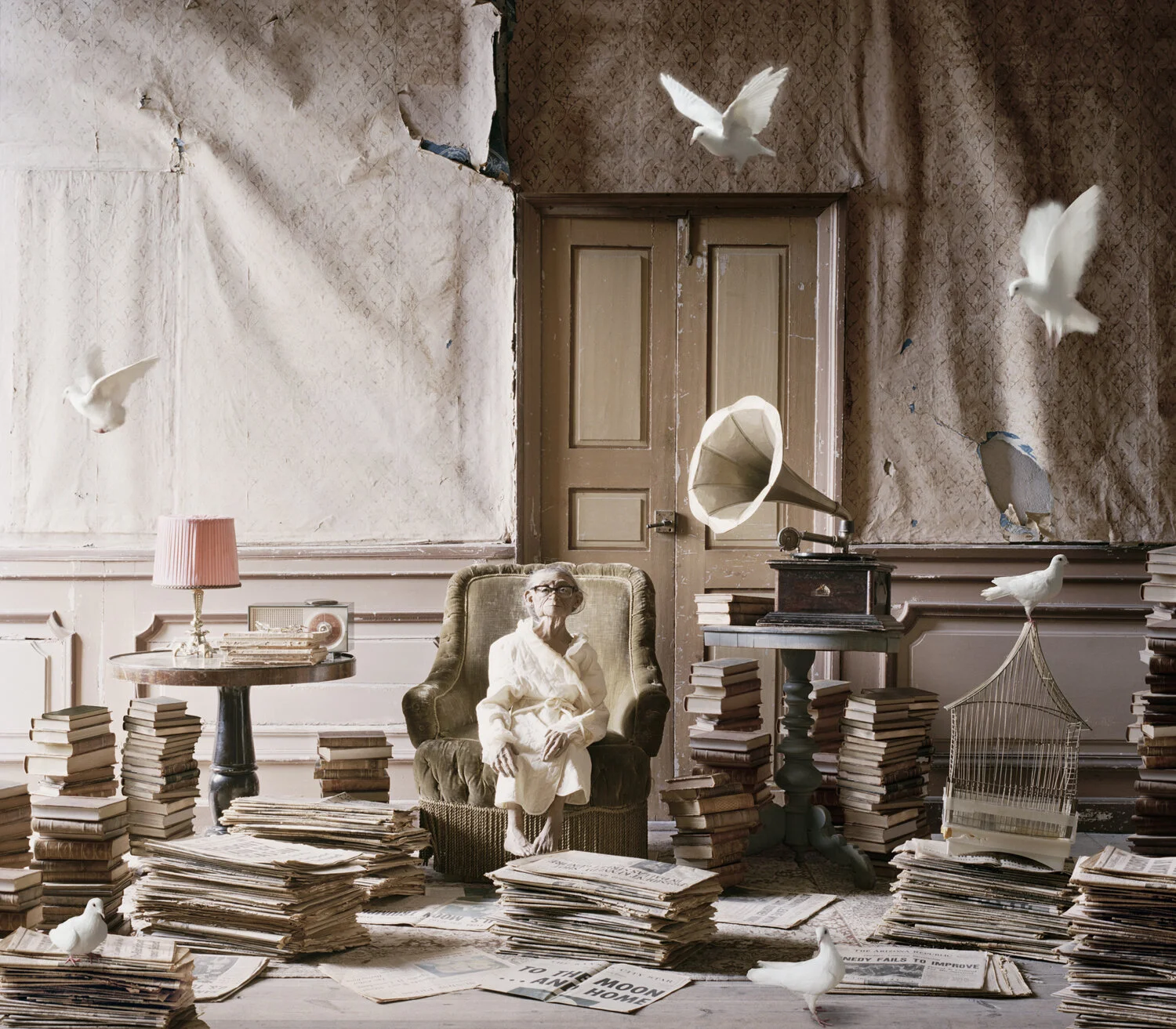

Cat/Bird

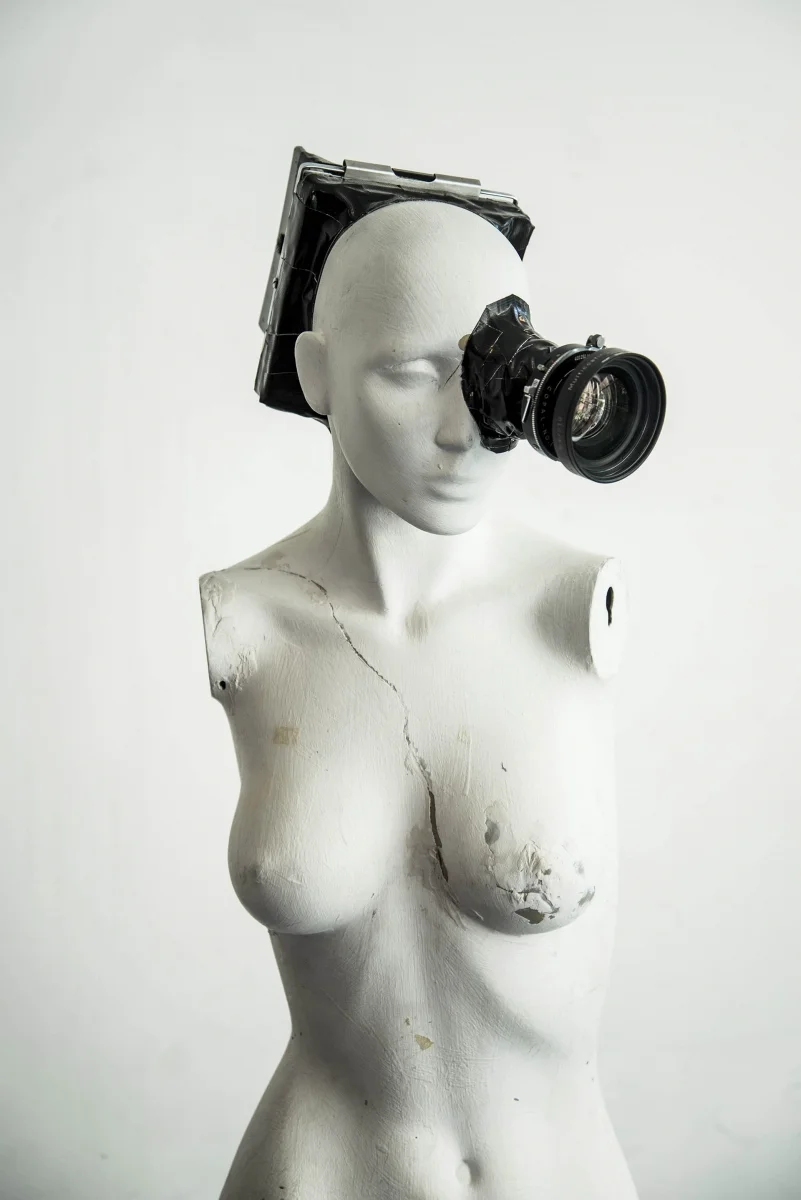

Last week I wrote about one of the two current photography exhibits at MOMA. Since visiting the exhibitions, I have been unable to stop telling the story of Robert Heinecken: Object Matter. If the studio-show navel-gazes at its formulating idea, the Heinecken show persuades me that a photographer whose work I have frankly always found a bit suspect is, in fact, near genius. Heinecken’s ability to transform the obscene into the loving utterly transformed my own thinking about his work and the craft. The exhibit is organized, at least in part, to provide access to the wide array of processes Heinecken employed in making his work. The impressive strategies he deployed while hashing out ideas will leave you at times amazed and at other times quaintly nostalgic for older media. The heart of the show, though, is not process, nor even idea, but genuine wrestling with complex internal impulses. Yes, there is plenty of satire here, and there is profound critique of a culture of consumption and voyeurism, but there is also tenderness of touch, disarming intimacy, and achingly beautiful sorrow. Yes, of course I saw “Cat/Bird” sitting up there dismissing me, and yes, I saw that milk pouring from that stunning mouth into Wahberg’s tighty-whities, but I also saw Reagan as a phantom reduced to color, light, and, to invoke Stevens, “ghostlier demarcations, and keener sounds.” We could spend days commenting on the explicit sexuality of the exhibit, but if we are going to comment on the lasciviousness of an erection, we must also comment on the sublime look of longing and tender gazes. Both emerge in this show.

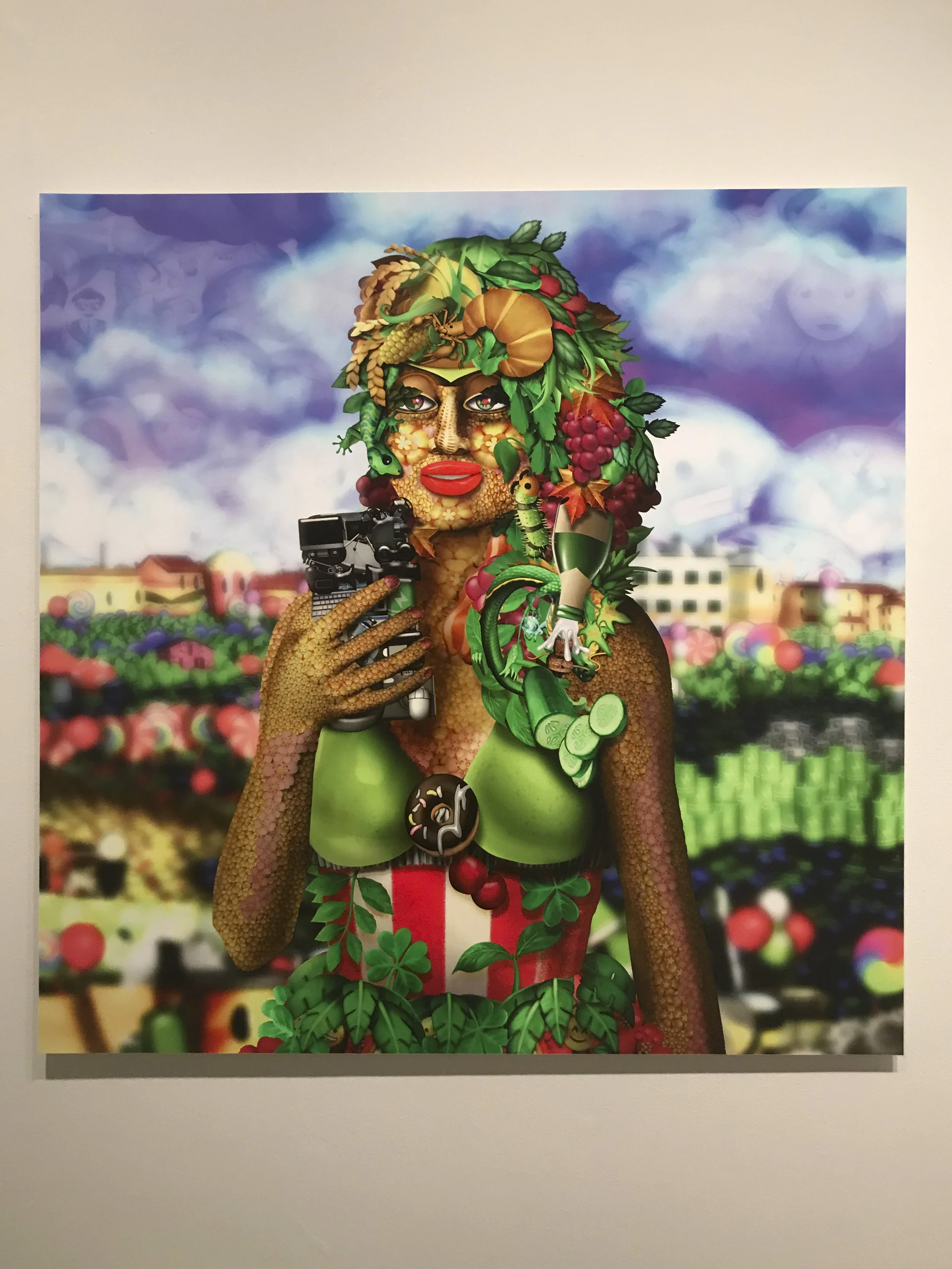

S. S. Copyright Project: "On Photography"

The impulse to fixate on singular aspects in the imagery, however, is precisely the impulse that this curation fights against, and it’s precisely why I find myself so struck by it in a way that the other exhibit wasn’t able to approach. In the same way that Heinecken’s “S. S. Copyright Project: ‘On Photography’” layers meaning by giving us a big picture that we can recognize and feel alongside minute images that, even when cut and sliced and stapled, insist on being seen and examined, so too does the exhibit ask us to pan out for a fullness of experience. Yes you’ll leer, and absolutely you’ll lean in to get a better look at that—was I right?—nipple, but when you leave, you won’t be thinking about that. You’ll have in your mind the big picture, and you’ll have been persuaded that not only were you wrong about Heinecken, but that you were hypocritical in your approach to our culture’s relationship to sexuality, the body, consumption, and love. If Heinecken “revised” magazines by splicing in the most provocative of images, he fundamentally changes photography by cutting in unexpected compassion and surprising vulnerability. Try to leave the exhibit without genuine love for the subject of “She: You’re like an animal.” And by genuine, I mean a sense that, through one photo and one written exchange, you have witnessed power that lies in the unexpected turn of the lens toward yourself. The subject is, after all, looking at you, and she does so longingly. You are now part of the show, and you won’t regret a moment of it when you wander away.

She: You're like an animal.

Roger Thompson is the Senior Editor for Don’t Take Pictures, an art critic, and a Professor at Stony Brook University in Long Island, NY.