Museums and universities hold some of the world’s best photography collections. Unlike works owned by private collectors, these institutions have a mission that includes sharing their collections with the public. But due to exhibition schedules and space constraints, many exquisite works are kept in storage for most of their lives. This series asks museum and university curators to mine their institution’s archives and share a selection of photographic works online for Don’t Take Pictures.

Founded by Columbia College Chicago in 1976, the Museum of Contemporary Photography (MoCP) collaborates with artists, photographers, communities, and institutions locally, nationally, and internationally. The MoCP’s permanent collection, comprised of over 14,000 objects, embraces a wide range of contemporary aesthetics and technologies, and the works are heavily accessed by students, educators, research specialists, and general audiences in its very active print viewing program.

Initially, the MoCP’s permanent collection defined “contemporary” as works made by American photographers since the 1950s. In the early 2000s, the date was pushed back to include the Farm Security Administration works of the 1930s and works by international artists. Because of its initial narrow collection focus, the MoCP is now taking large strides to expand its holdings of works by international and minority, artists, specifically focusing on women artists and African, Asian, Latin American, Islamic, and Native American art.

The works highlighted here are by women artists who have been in the MoCP’s collection for years—or decades—but that have rarely or never been included its exhibitions.

Carlotta Corpron (American, 1901-1988), Black and White Box, 1945; 1993:28

Carlotta Corpron (American, 1901-1988), Glass Springs, 1945; 1993:26

During a period of intensive creative activity in the 1930s and 40s, Carlotta Corpron investigated the expressive potential of light in six successive series of photographs. Initially she experimented with solarization techniques and used the camera to record moving lights, making what she called "light drawings." In the mid-1940s she began to concentrate on studies of light in a controlled studio setting. During this period the influential artists László Maholy-Nagy and Gyorgy Kepes, who were known for their photographic abstractions, relocated to Denton, Texas, where Corpron was teaching at Texas Women's University. In 1942 Corpron conducted a "light workshop" at the university under the direction of Maholy-Nagy, who was one of the pioneers of the photogram, but it was Kepes, Maholy's former colleague, who influenced Corpron after his arrival in 1944. For a number of months Corpron met frequently with Kepes, who praised her work and which he described as "light poetry."

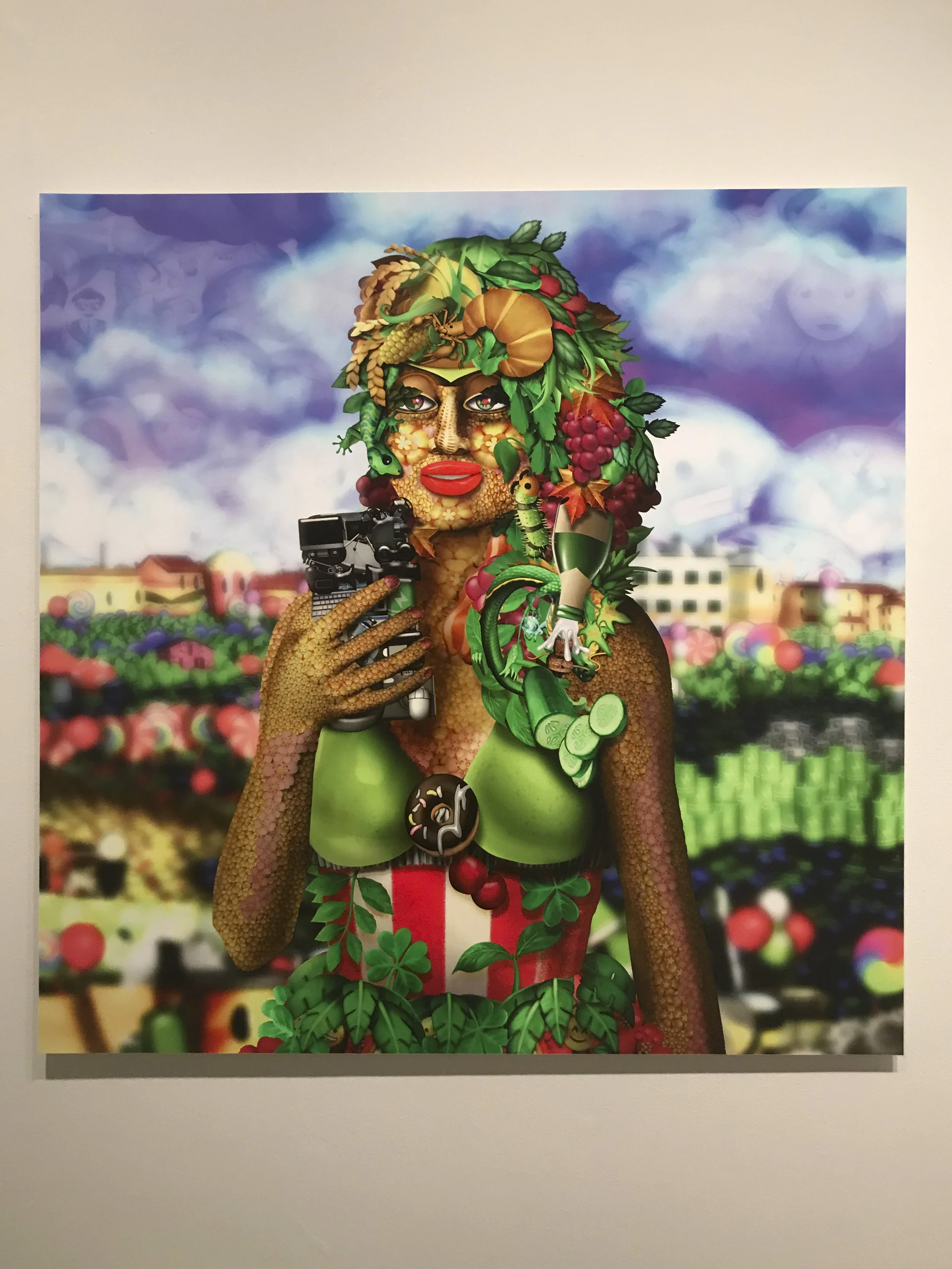

Graciela Iturbide (Mexican, b. 1942), Notre-Dame des Iguanes, Juchitàn, Oaxaca, 1979; 2007:337

Graciela Iturbide is famous for her pictures of Mexico, particularly its indigenous population, though later projects have taken her to India and the American South in her exploration of modern culture. In particular she is known for her master work Juchitán of Women, a decade long project begun in 1979 when artist Francisco Toledo invited a group including Iturbide to visit Juchitán, a small town in southern Mexico's Tehuantepec Isthmus. This Zapotec Indian town had a distinct culture and way of life, notable for the dominance of women in commercial and political spheres.

Marilyn Bridges (American, b. 1948), Thira, Greece, 1984; 2011:307

Marilyn Bridges (American, b. 1948), Farmer's Edge, South Dakota, 1984; 2011:314

In 1976, upon seeing the Nazca Indian "runway" lines in Peru, Marilyn Bridges decided to become a pilot. Bridges is credentialed to fly single- and multi-engine land and sea aircraft, and she even owns her own Cessna, but she does not pilot when she photographs. Waiting for just the right light, she directs the pilot where to fly and when to tilt in angles ranging from low oblique to vertical to get the right picture. The process is technically demanding both in terms of flying--the plane must slow down to just a notch above stalling even at a shutter speed of 1/1000th of a second--and in terms of photographing. Unable to slow the plane any more than she does, Bridges extends the speed of her Tri-X film by pushing it (a development technique). So that her landscapes resonate as land and not as abstractions, she shoots from an altitude no greater than 1000 feet above the earth, and she prefers to get as close as 200 feet. She usually shoots with a 6×7 Pentax medium-format camera, sometimes a Leica 35mm, and always from an open window.

Lalla Essaydi (Morroccan, b. 1956), Converging Territories #11, 2006; 2007:137

According to Islamic tradition public spaces are a male domain and women are largely limited to the private sphere. In the “Converging Territories” series, Lalla Essaydi makes large-scale photographs of Moroccan women within a stylized domestic space. Essaydi challenges the traditional social boundaries and gender dynamics by writing calligraphy in henna across women's clothes, their skin wherever it is visible, and every inch of their surroundings. She states, "In photographing women inscribed with henna I emphasize their decorative role, but subvert the silence of confinement. These women 'speak' visually to the house and to each other, and create a space that is both hierarchical and fluid. Furthermore, the calligraphy, a sacred Islamic art form inaccessible to women, constitutes an act of rebellion. Applying such writing in henna, a form of adornment considered 'women's work,' further underscores the subversive nature of the act."

Kristin Taylor is the Manager of Collections for the Museum of Contemporary Photography at Columbia College Chicago.